High-Level Thoughts

The book is both terrifying and surprisingly optimistic – Terrifying in how bleak our future could be if we continue to abuse our planet in the way we’ve grown accustomed, and optimistic in how it’s possible for change before it’s too late.

Attenborough has spent a lifetime documenting our planet and its wildlife. He’s witnessed first-hand the changes that have taken place as our species has rapidly developed and he lays out the grim reality of these for us to see. The decimation of natural habitats, pollution of the atmosphere, pollution of the ocean, overfishing and general loss of wildlife, and more. All markers of human dominance; All caused by our continued pursuit of growth and progress. We’ve caused so much harm to our planet that it’s now reached a crisis point. Whether we like it or not, humanity has great influence over how this crisis plays out.

The book lays out two paths for our future. The first, more depressing path, is one where we continue living as we currently do, destroying the planet in the process until we reach a point where our very survival is in question. The second, more optimistic path, is the one Attenborough spends the latter half of the book advocating for – the path of a sustainable existence. This is where we, as a global species, band together to change our ways in order to save not only our planet but also ourselves.

Despite the potential for a positive future that’s laid out in the book, I find myself emotionally conflicted. I want to be optimistic about our future. Optimistic that we can band together, undo the climate crisis, and save our planet – all whilst we still have time to do so. But at the same time, I’m fearful that it’s just a pipe dream. A lot of the changes we’d need to make are monumental in nature. They’d impact people globally in a variety of ways and likely cause a lot of hardship for people in the process. In my experience, the larger a change is, and the more uncomfortable the change makes us feel, the less likely we are to do it. Whilst it’s not impossible for us to band together and move towards a sustainable existence, it will be a monumentally difficult task to complete – one that might not be completed in time.

Key Ideas

- The climate is evidently in crisis and, depending on how we act, we can either save it or destroy it.

- The Doughnut Model provides a good indicator of where we should focus our efforts if we are to both improve global living conditions whilst simultaneously healing the environment.

- A key area of focus should be on ‘rewilding’ the planet. The more wilderness we have, and the more biodiverse said wilderness is, the more capable it will be of removing carbon from the atmosphere.

- Moving to a more plant-based diet, one where we consume significantly less red meat, would help reduce the amount of farmland we need. Not only would this provide more space to rewild, but it would also reduce our emissions considerably.

- We should aim for sustainability in all things.

Book Summary

Introduction

David Attenborough is perhaps the world’s most recognisable naturalist, having spent his career producing captivating documentaries that bring the natural world to us in the comfort of our own homes. Through his work, he’s witnessed first-hand the impact our ever-evolving lifestyles have had on our planet. Whilst a lot of the changes in our lifestyles have had positive impacts on us – improved healthcare, more advanced technology, easier access to transport and travel, and so on – they’ve had a tremendously negative impact on the natural world.

Whilst the impending climate catastrophe has become more publicised in recent years, the damage we’ve had on the natural world has been manifesting for decades. Throughout the course of Attenborough’s life, the world has witnessed: Animal and insect populations reducing in size, coral bleaching, damage to the ozone layer, shrinking polar ice, smaller fishing hauls, reductions in global wilderness areas, increased pollution and waste, and much more. All of these changes can be attributed to the growing global population and the drastic lifestyle changes our species has undergone.

Since Attenborough’s birth in 1926, the global population has almost quadrupled in size. To sustain our growth, we’ve steadily removed the planet’s wilderness so that we can have more space to live. But we’ve not done this in a sustainable way because, in addition to removing the wilderness, we’ve also been steadily releasing more and more carbon into the atmosphere. Despite knowing this, the figures below show there’s no sign of us slowing down just yet;

| Year | World Population (Billion) | Carbon In The Atmosphere (parts per million) | Remaining Wilderness (%) |

| 1937 | 2.3 | 280 | 66 |

| 1954 | 2.7 | 310 | 64 |

| 1960 | 3.0 | 315 | 62 |

| 1968 | 3.5 | 323 | 59 |

| 1971 | 3.7 | 326 | 58 |

| 1978 | 4.3 | 335 | 55 |

| 1989 | 5.1 | 353 | 49 |

| 1997 | 5.9 | 360 | 46 |

| 2011 | 7.0 | 391 | 39 |

| 2020 | 7.9 | 415 | 35 |

Having spent his life documenting the natural world, witnessing these changes first-hand, and learning of how our actions directly impact them, Attenborough lays out the current state of the world (as of 2020), a grim prediction for humanities future should we continue on the course we’re on, and some guidelines of how we may change to safeguard humanities future.

The World in 2020

As of the release of the book, humanity is living in a way that the planet can’t sustain for much longer:

- We extract over 80 million tonnes of seafood from the oceans each year.

- Such overfishing has contributed to 30% of fish stocks reaching critical levels.

- Almost all large oceanic fish have been removed from the ocean.

- Coastal developments, alongside seafood farming, have reduced the extent of the world’s mangroves and seagrass beds by more than 30%.

- We’ve already lost around half of the world’s shallow-water corals.

- Of what remains, major coral bleachings occur almost every year.

- Our species leaves more waste and debris in its wake every year.

- Plastic debris litters the ocean. In the northern Pacific, a garbage patch circulates containing roughly 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic.

- No beach on Earth remains free from our waste.

- Plastic invades the oceanic food chain. Over 90% of seabirds have fragments of plastic in their stomachs.

- Freshwater systems are as threatened as marine systems.

- We’ve interrupted the free flow of almost all sizable rivers thanks to over 50,000 large dams.

- We’ve inadvertently loaded rivers with fertilisers, pesticides, and industrial chemicals. All of which we originally use on land but will drain into rivers nonetheless.

- We’ve drained wetlands to such an extent that their global area is roughly half of what it was when Attenborough was born.

- We’ve reduced the size of animal populations in freshwater systems by over 80%.

- We cut down 15 billion trees annually.

- The world’s rainforests have been reduced by half.

- The remaining forests and woodlands are fragmented by roads, farms, and plantations.

- Beef production remains the number one driving cause of deforestation – almost double the next three greatest causes combined. The second greatest cause is soy production, but over 70% of soy is used to feed the livestock we consume.

- Half of all fertile land on Earth is now farmed.

- In the last 30 years, global insect numbers have dropped by a quarter.

- In places where pesticides are used, this number is higher.

- 70% of the mass of birds on Earth are domesticated.

- The vast majority of this is formed by chickens, of which we consume 50 billion globally. 23 billion chickens are alive at any given moment.

- 96% of the mass of all mammals on Earth is made up of our bodies and the bodies of animals we raise to eat.

- Our own mass alone is only one-third of this total.

- Since the 1950s, on average, wild animal populations have more than halved.

As things stand, these problems are set to continue. We live in a way that takes a great deal from the natural world, all whilst giving very little back. And given our species’ proclivity towards perpetual growth in all things we pursue, we’ll inevitably take even more from nature. But things can’t continue this way forever. Our world is a closed system. Its resources, finite. And as Attenborough puts it

“For on a finite planet, the only way to achieve perpetual growth is to take more from elsewhere. What felt like a miracle of the modern age was just stealing.”

If we continue to steal from the planet, it’ll reach a point where it can no longer provide for us. If we reach that point, the consequences for us are dire.

Our Future if we Don’t Change

Continuing to take from the planet in the way we’ve grown accustomed to will only lead to a bleak future for humanity. For a while, the Earth will continue changing gradually. But it will eventually reach a point where the consequences of our actions will compound so heavily that the changes will come more rapidly. Without changing, this is what the future holds:

- At the current rate of aggressive deforestation, in the 2030s the Amazon rainforest will be reduced to 30% of its original size.

- This could prove to be the tipping point that leads to forest dieback.

- The loss of the Amazon means the loss of the wildlife species it supports. We could lose species that may have yielded new drugs or foodstuffs, all before we even know they existed.

- The loss of the rainforest could lead to erratic flooding in the Amazon basin which, in addition to damaging the rivers, would force thirty million (including 3 million indigenous people) to relocate.

- The food production in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, and Paraguay would be radically impacted.

- It’s estimated that the Amazon’s trees have locked away 100 billion tonnes of carbon. All of this would be released back into the atmosphere, further contributing to global warming.

- Also in the 2030s, the Arctic Ocean is anticipated to have its first ice-free summer.

- The loss of ice means that the algal forests, which currently reside beneath the ice, would be cast into the ocean, disrupting the entire Arctic food chain.

- No new ice means more water at the poles in addition to the reduction in the ice sheltered at fjords.

- Less ice means the Earth will be less white. Consequently, it would reflect less of the sun’s rays leading to the planet warming even more rapidly.

- Thie continually warming planet will reach a point, currently anticipated to be during the 2040s, where the permafrost in places like Alaska, Russia, and northern Canada will begin to melt.

- This is potentially far more hazardous than the melting sea ice. As much as 80% of the soils in these regions is comprised of frozen water. The melting ice would result in the appearance of new lakes, craters in the earl, and the land generally sinking.

- It would also cause massive landslides and flooding. Rivers would change course and the silty freshwater would flow out into the sea, impacting the local wildlife and people.

- Worse still, the permafrost holds an estimated 1,400 gigatonnes of carbon – 4x what we’ve emitted over the last 200 years. All of this would be released into the atmosphere, further accelerating global warming.

- By the 2050s, our carbon pollution would have turned the ocean sufficiently acidic to trigger a calamitous decline in oceanic wildlife.

- Coral reefs, the most diverse of all marine ecosystems, are particularly vulnerable to acidification. Some predict that we could lose 90% of coral reefs within the span of a few years.

- Acidification would also have a catastrophic impact on the oceanic food chain. The increasing acidification would inhibit the ability of many species of plankton to bloom. Fish all the way up the food chain would suffer as a result.

- The loss of fish populations could prove to be the end of commercial fishing.

- By the 2080s, global food production on land would be in crisis.

- The cooler parts of the world habitually employ intensive agriculture methodologies which exhaust soils of their nutrients. This inevitably causes many crops to suffer and, perhaps, even fail entirely.

- Warmer climates would suffer due to the higher temperatures, changes in monsoons and storms, and general droughts. All of which contribute to crop failure.

- At our current rate of pesticide use, combined with habitat removal and diseases in pollinator species, insect species will suffer such tremendous losses that it could impact a quarter of our crops.

- The 2100s could begin with a global humanitarian crisis.

- The rising ocean waters will force coastal cities to become abandoned, leading to mass migrations further inland.

- If everything listed above transpires, the planet would be 4°C warmer. An average temperature of 29°C would be experienced in places where a quarter of the human population reside. As of today, this level of daily heat scorches just one place – the Sahara.

- The rise in temperature would make farming impossible in warmer climates. Attempting to ensure people are fed will overburden the cooler climates where farming may still be possible.

- Given all of this, the sixth mass extinction event could be well underway.

Whether or not this transpires is up to us. If we want to avoid the above then we must act now. We must change how we live. But how should we change? What areas do we need to focus on? And what exactly should we change? Luckily, there’s a rough guide for this.

A Compass to Guide Our Change

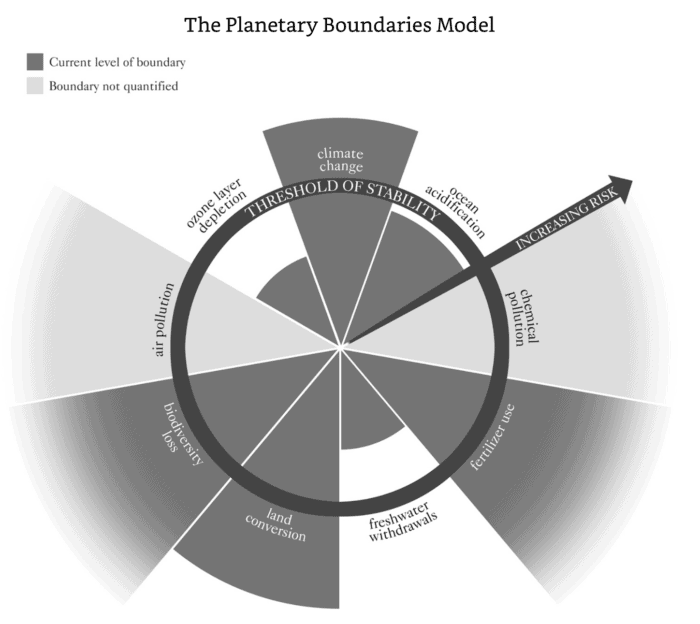

After studying the resilience of the Earth’s ecosystems, a team of leading Earth system scientists led by Johan Rockström and Will Steffen, found nine thresholds seemingly hard-wired into the Earth’s environment. Remaining within these thresholds would allow for a sustainable existence. Moving beyond them would not. In a sense, they are natural boundaries to our activities.

As Attenborough notes, “Currently, our activities are committing the Earth to failure. We have already pushed through four of the nine boundaries. We are polluting the Earth with far too many fertilisers, disrupting the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles. We are converting natural habitats on land – such as forests, grasslands, and marshlands – to farmland at too great a rate. We are warming the Earth far too quickly, adding carbon to the atmosphere faster than at any time in our planet’s history. We are causing a rate of biodiversity loss that is more than 100 times the average, and only matched in the fossil record during a mass extinction event.”

This model gives us a good indicator of what we need to change in order to have a more sustainable existence – but it misses something important. The model only looks outward at the state of the natural world. In so doing, it overlooks our own needs.

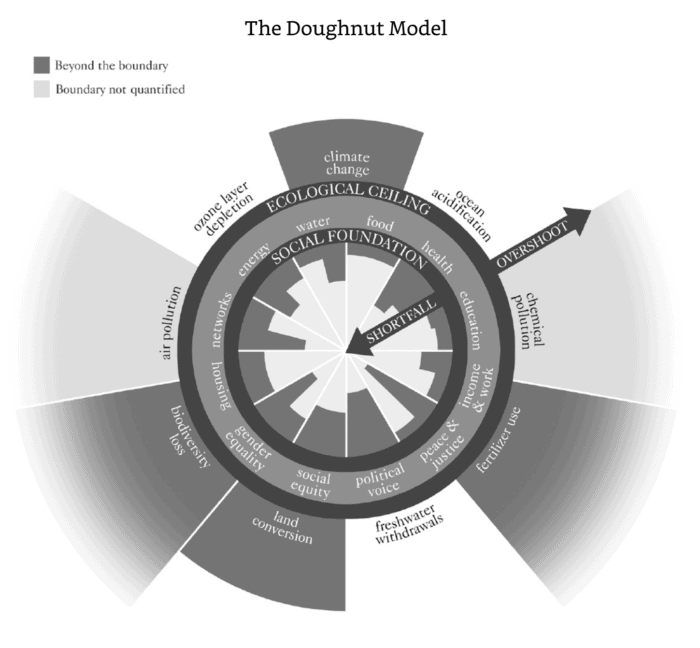

University of Oxford economist Kate Raworth challenged this by adding an inner ring to the model. This inner ring holds the minimum requirements for human well-being. Looking at this new model, the Doughnut model, we have a more precise guide on how to live a sustainable existence. The upper boundary places a limit on our actions whilst the lower boundary sets the minimum standard we should strive for to afford everyone a good standard of well-being.

The challenge this sets out for humanity is this: to improve the lives of people everywhere whilst simultaneously radically reducing our impact on the natural world.

Attenborough argues that if we want to rise to this challenge, then we should look to nature for inspiration. In particular, he focuses on four key things: Moving beyond growth, moving to clean energy, rewilding the world, and planning for peak human.

Moving Beyond Growth

It’s undeniable that things in the natural world grow. Be it individuals, populations, or habitats. But what we tend to overlook is that after a period of growth, things in nature tend to mature. They stop growing and begin to thrive. And, what’s more, is that it’s entirely possible to thrive without necessarily getting bigger. Something our species seems to have overlooked.

Much of our current predicament can be attributed to our desire for perpetual growth. There’s also no indication that we want to stop growing and reach our comfortable, mature plateau. In fact, for the past 70 years, many of humanities institutions have adopted growth as an overriding goal – measured by gross domestic product (GDP).

Growth wouldn’t be a bad thing, were it not for the impact it has on the world around us. As mentioned earlier, we’ve taken everything we have from the natural world. We deforest, overfish, emit greenhouse gases, discard plastic waste, and so on. We now face a challenge; can we continue to grow without exploiting the natural world? If we can’t, can we somehow move beyond growth to a mature plateau?

One potential avenue to explore is “green growth”. For this, economic growth is still our predominant goal, however, unlike our current approach, we’d look to separate it from adverse environmental impacts and the use of fossil fuels. Unfortunately, this won’t happen without a deliberate effort on our part. One impetus that could set us on this path would be for politicians and business leaders to stop subsidising damaging industries in favour of ones that are more sustainable.

Yet, despite its noble intentions, green growth is still growth. If we ever wish to enter a mature plateau, we’d have to abandon our addiction to growth. Some hope that we’ll one day achieve this by abandoning GDP in favour of new metrics that combine profit, planet, and people as our measure for success. Some attempts have been made on this front already, such as the Happy Planet Index laid out by the New Economics Foundation in 2006. Metrics like these encourage debate around GDP and the sum purpose of humanity’s efforts on Earth. Hopefully, with time, such metrics and debates will lead to global change.

Moving to Clean Energy

As of 2019, fossil fuels still provided 85% of our global energy. Whilst the use of renewables may be on the rise, we’re still relying far too heavily on fossil fuels and subsequently overloading the carbon in our atmosphere. In effect, we’re replicating the changes that led to the mass extinction event at the end of the Permian – only, we’re bringing the changes about far more rapidly.

Our careless use of fossil fuels has already caused the temperature of the planet to rise by 1°C from pre-industrial levels. Our current aim is to halt any further rise at 1.5°C. But to successfully do this we must limit the amount of carbon we add to the atmosphere. In essence, we have a carbon budget – a budget we’re on track to fully use by the end of the decade. If we wish to delay this, then we must hasten the transition towards clean energy.

We’re now at a point in time where we have practical access to clean energy. But a complete transition still poses challenges that must be overcome. Firstly, there’s a storage problem. Current battery technologies aren’t adequately developed to meet our storage and supply needs. Secondly, renewables aren’t yet efficient enough to fully provide for things like heating, cooling, or transport. Both of these mean that we will need to rely on fossil fuels to meet any shortcoming of supply, but we should only do this as a temporary solution. Our aim should be to sufficiently develop our technologies to overcome these hurdles.

Another potential obstacle is affordability, but over time this will pass naturally. As solar and wind power have scaled up, it has brought the price of renewable energy per kilowatt to levels that can outcompete coal, hydro, and nuclear. It’s also rapidly approaching that of gas and oil. In addition to this, it’s estimated that, over a 30-year period, a renewable-dominated energy sector could save trillions of dollars in operational costs.

But the most formidable obstacle the transition to clean energy faces is us. There is too much vested interest in the existing energy industry. Of the 10 largest companies in the world, 6 are oil and gas companies. Additionally, many other companies and governments are reliant on fossil fuels for both power and distribution needs. Banks and pension funds are also known to invest in such companies and industries too. In short, a change to the system would have widespread disruptions outside of the energy industry itself. And the more disruption a change causes, the more reluctant we as a species are to adopt it.

Rewilding the World

Of all the solutions discussed, ‘rewilding’ is the one that’s advocated for most. This is because it benefits us on multiple fronts. As Attenborough puts it,

“The rewilding of the world will suck enormous amounts of carbon from the air and lock it away in the expanding wilderness. When executed in parallel with global cuts in emissions, this nature-based solution would be the ultimate win-win – carbon storage and biodiversity gain all in one. Studies in many habitats have shown that the more biodiverse an ecosystem, the better it captures and stores carbon.”

In other words, rewilding would help revert some of the biodiversity loss we’ve helped cause whilst simultaneously helping us to remove mass amounts of carbon from the atmosphere; carbon that we put there in the first place. If we’re going to rewild the world, then we’ll need to take different approaches for land and sea.

Rewilding the Seas

The ocean plays a special role in rewilding the world. It covers two-thirds of our planet and its depth offers an even greater proportion of inhabitable space than land does. Rewilding the ocean would therefore benefit us on three fronts – improved carbon capture, increased biodiversity, and increased food supply. That last one’s particularly important.

Throughout human history, the ocean has provided an ample supply of food for us. But since our technological revolution, we’ve overburdened our oceans to the point where 90% of fish populations are either overfished or fished to capacity. Continuing to fish as we do, we risk pushing things to a point where fish stocks are permanently poorer. And as the global population continues to rise, food supply will become a more important issue – losing access to the ocean could prove detrimental to our future.

Whilst this may make it sound like fishing needs to be stopped, we need not be that extreme. After all, rewilding would lead to a healthier and more biodiverse ocean which leads to more fish. And if there’s more fish, there’s more for us to eat. But if it’s so simple, why isn’t it working like this right now? Well, “we fish some places and some species too much. We waste too much. We use clumsy fishing techniques that wreck the ecosystem. And most damaging of all, we fish everywhere.” By assessing these problems, we can see what we can change to help the rewilding process.

The first thing we should consider is a network of no-fish zones or Marine Protected Areas (MPA). We already have over 17,000 MPAs, but collectively these account for less than 7% of our ocean. Additionally, many MPAs still permit certain types of fishing to take place. If we want MPAs to have the most benefit, they need to ban fishing entirely.

If we leave fish in certain areas alone, then the fish will grow older and bigger. Bigger fish produce disproportionately more offspring. As the fish have more and more offspring, their population swells which forces it to overflow into neighbouring waters where we can then fish. This spill-over effect has already been observed around MPAs in the tropics and arctic, so we know it can work. It’s estimated that turning one-third of our oceans into MPAs would be sufficient to take advantage of this effect; thus, allowing the ocean to both recover and supply our needs.

But the question is, where should the MPAs be placed? The answer is again found by looking at nature. We should place them in the areas where marine animals find it easiest to breed – rocky and coral reefs, submarine seamounts, kelp forests, mangroves, seagrass meadows, and saltmarshes. There’s an added benefit to choosing these areas too – carbon capture. In their current depleted state, saltmarshes, mangroves, and seagrass meadows remove the equivalent of half of all our transport emissions from the air. If left to recover, they could remove even more.

With that tackled, it’s time to turn to how we fish. We need to move away from the idea of fishing for profit or growth and instead focus on the idea of fishing forever. In other words, fishing sustainably. To support this, we need more advanced fishing techniques than what we currently use. We could benefit from, to name but a few, having more sophisticated designs in netting that allow non-target species to escape. Larger predatory fish, such as tuna, should be pole or line caught. And we should ban the dredging of the seabed given its destructive nature. On top of all this, we should be actively monitoring key fish stocks and employing self-restrains to ensure we always keep within sustainable yields.

“If we stop overexploiting the ocean, and begin to harvest it in a way that allows it to thrive, it will help us restore biodiversity and stabilise the planet at a speed and scale we could not hope to achieve on our own.“ And in so doing, “the high seas would become the world’s greatest wildlife reserve, and a place owned by no one would become a place cared for by everyone.”

Rewilding the Land

As our species has developed, we’ve claimed more and more of the natural world for ourselves. We take as much land as we think we need, whilst spending little thought on what existed there before us. We tear down forests, drain wetlands, fence off grasslands, and so much more. All in the name of progress.

Farming has been one of the leading contributors to our land expansion. As our species has grown, so has our need to farm. Back in the 1700s, we farmed around 1 billion hectares of land. Today, our farmland is just under 5 billion hectares – a size equivalent to North America, South America, and Australia combined. Whilst this has benefited our species by providing more space to plant crops and raise animals, it’s been devastating for our planet. The conversion of wildland to farmland has been the single greatest direct cause of biodiversity loss during our time on Earth. Not only that, but it’s also one of the leading causes of greenhouse gas emissions. By tearing down forests, burning trees, dredging wetlands, and so on, we’ve reduced the amount of greenery that removes pollution from our atmosphere whilst simultaneously releasing two-thirds of historic carbon that nature captured and stored.

We need only look at our dietary choices to see why we’ve expanded our farmland so drastically. As people and nations become wealthier, their diets shift to become more meat dominant. This large consumption of meat is at the heart of our unsustainable demand for farmland.

Of the 5 billion hectares of land we farm, 4 billion of it is used for meat and dairy production. What might surprise some is that much of that land has no livestock in it at all. Instead, it’s dedicated to crops, like soy, with the intention of being used exclusively to feed cattle, chickens, and pigs.

Of all the meats we raise, beef is by far the most damaging on average. Beef makes up around a quarter of the meat we eat and only around 2% of our calories. Yet we dedicate 60% of our farmlands to raising it. It occupies 15 times more land per kilogram than pork or chicken. As our populations continue to grow, it’s not going to be possible for every person to continue to eat the same amount of beef as is consumed now. Earth doesn’t have enough land for us to do so.

This is a good indication that if we intend to rewild the land, then changing our diets would be a good place to start. “A wealth of research has already been done to deduce what kind of diet would be fair, healthy, and sustainable – both good for people and good for the planet. The universal option is that in the future we will have to change to a diet that is largely plant-based with much less meat, especially red meat.” This reduction in meat would benefit us on multiple fronts. The two most obvious would be that it would drastically reduce the space we need for farmland whilst also leading us to produce fewer greenhouse gases. But the less obvious one is that it could improve our health. Some studies suggest that a diet with less meat in it could reduce deaths from heart disease, obesity, and some cancers by up to 20%.

Such a change wouldn’t be without its drawbacks. Animal rearing and eating meat are important parts of many cultures, traditions, and social lives. Not to mention that it provides livelihoods for hundreds of thousands of people globally, and in some areas, there is no current alternative. So, when we make this change, we have to do it in a way that helps safeguard these people lest we leave people in potentially dire situations.

Regardless of whether we can reduce our farmland or not, we need to look at ways of improving the biodiversity of our land in order to undo some of the damage we’ve already caused. One way we can look to do this is by rebuilding many of the forests we’ve destroyed.

Deforestation has been an emblem of our dominance. It’s so closely linked to humanity’s progress that there’s a recognised model to define it – the forest transition. As a nation begins to develop, we rapidly deforest for numerous reasons – wood for fuel, wood for trade, and increased space. As a nation becomes more developed, the rate of deforestation begins to slow until it reaches a post-transition stage wherein reforestation begins to occur.

Many affluent countries have reached this reforestation stage. One of the reasons they’re able to do this is globalisation. Wealthier nations are able to import many food crops and timber from less-developed nations. Unfortunately, this means that these less-developed nations continue to deforest. Many of these nations in the tropics are chopping down the deepest, darkest, and wildest forests of all – the rainforests. If their forest transition runs its course, it will be disastrous for the planet. The carbon it will release into the atmosphere, the loss of trees that suck carbon back out, and the species loss it would cause would be catastrophic.

The challenge we face is halting deforestation whilst ensuring less-developed nations don’t suffer in consequence. Sadly, it’s easier said than done. Unlike the oceans, which are owned by no one, the land is portioned into billions of different-sized plots and owned by people, corporations, and governments. As such, the land has value. A value which is decided by our markets – and this is the heart of our problem.

Currently, there’s no way of calculating the value of the wilderness and the environmental services it provides. On paper, one hundred hectares of rainforest will have less value than one hundred hectares of oil palm plantations. The only real solution to this is to change the meaning of value, but this too is a tricky problem to solve. REDD+ is one attempt to do this. It looks to give a proper value to the worlds remaining rainforests by pricing the immense amount of carbon they store, rather than the value it purely on the profit that can be made from the land it resides on. But all this does is shift the definition of value from money to carbon capture, which doesn’t entirely solve the problem. The goalposts shift but the game stays the same, thus allowing people to continue its exploitation for personal gain. We must look to refine such systems and adopt them more widely if we want them to have any benefit.

Planning for Peak Human

All of our strategies discussed thus far have been concerned with reducing our footprint, thus enabling the wild to return. But for this to be successful, we have to take into account our own population. As our population size increases, so does our demand for resources from the planet. We’ve grown from roughly 2 billion in the early 1900s, to around 8 billion today. Whilst our growth does appear to be slowing down, it shows no sign of stopping as of yet. Current UN projections place the population at somewhere between 9.4 and 12.7 billion people by 2100.

In nature, animal and plant populations in a given habitat remain roughly stable across time. They find a balance with the rest of their habitat’s community. If a species has too many individuals, they find it harder to get what they need from a habitat. When this happens, a few will die or leave the habitat. If there are too few of a species, and an abundance of resources available to them, they breed until the species reaches its full potential. In general, this causes an oscillation in species population – it grows, shrinks, grows, shrinks. This oscillation takes place around a number that the environment can sustain indefinitely. That number is the carrying capacity of the environment for that particular species. In essence, the carrying capacity is the balance in nature.

Unlike any species in the wild, humanity has yet to find Earth’s carrying capacity. Whenever we think we’re meeting it, we tend to invent or discover new ways to provide the essentials that support our existence. In that way, it may seem like there is no carrying capacity for humanity and that nothing can stop us. But “the catastrophe unfolding around us surely suggests that there is. The loss of biodiversity, the changing climate, the pressure on the planetary boundaries, everything points to the conclusion that we are finally fast approaching the Earth’s carrying capacity for humanity.”

But there’s another problem. Even before reaching Earth’s carrying capacity, we’re consuming too much. “Since 1987, an Earth Overshoot Day has been announced – an illustrative date in the calendar on which humankind’s consumption for the year exceeds the Earth’s capacity to regenerate those resources in that year. In 1987 we were over-shooting the Earth’s resources by 23 October. In 2019, we were doing so by 29 July.” This overshoot is at the heart of our unsustainability. By overshooting, we’re artificially lowering Earth’s carrying capacity by eating into its resources too heavily. By reducing our consumption, and our impact on the planet, we will effectively raise the carrying capacity back up.

But for this to succeed, it’s important for human population growth to level off. Is there a way for us to force this to happen? Well, evidence suggests there might be.

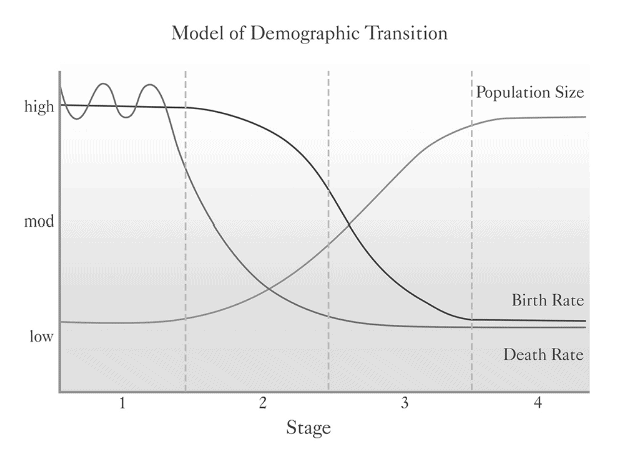

Geographers have a term, demographic transition, that describes the path nations follow during their economic development. This has four stages, each marked by changes in the population’s birth and death rates.

Stage 1 is pre-industrial, where a society relies heavily on agriculture and is thus more vulnerable to disasters such as drought or disease. Here, the birth rate is high but so is the death rate. As a country industrialises, it moves through these stages until the population begins to stabilise. Here, both birth and death rates are low.

If we follow this, then it would suggest that the faster a nation develops then the sooner its population will peak. It may even peak at a lower number than if the transition takes a longer time. But what form should this take? “In practical terms, this means helping the least developed nations achieve the ambitions in the Doughnut Model as fast as possible – supporting people as they raise themselves out of poverty, building healthcare networks, education systems, better transport and energy security, making these nations attractive to investment – anything, in fact, that improves the lives of people.”

Of all the possible improvements, one in particular has been found to significantly reduce family size and, therefore, population size. The empowerment of women. Wherever women have the right to vote, an education, access to healthcare, contraception, have the power to lead their own lives and make their own decisions, and so on, the birth rate falls. Empowerment brings freedom of choice and when life offers more choices, their choice is often to have fewer children.

Another avenue to explore is education. “Research at Austria’s Wittgenstein Centre has demonstrated how dramatically a strong multinational effort to raise the standards of education across the world would change the course of human population growth.” One of their forecasts calculated what would happen if the education systems in the world’s poorest nations were rapidly improved. The output was that humanity’s population could peak as soon as 2060, with a size of 8.9 billion. This is far lower than the predictions of the UN and could potentially be achieved simply by investing in education.

Both of these avenues help limit population growth. But they’re not just about population size. They’re also about committing us to making a fair and just future for all. Giving people more opportunities in life is surely something we want to be doing anyway. And if it also helps us reach our peak population sooner, and thus cap our footprint sooner, then it’s a win-win for humanity.

Conclusion

We’re at a pivotal point in human history. One where we can either contribute to our own destruction or, alternatively, pave the way for a brighter, healthier, more sustainable existence for humanity. We’re currently on the path of destruction, however, “we can yet make amends, manage our impact, change the direction of our development and once again become a species in harmony with nature. All we require is the will. The next few decades represent a final opportunity to build a stable home for ourselves and restore the rich, healthy and wonderful world that we inherited from our distant ancestors. Our future on the planet, the only place as far as we know where life of any kind exists, is at stake.”